One of the primary reasons people establish a financial plan is to make sure their hard work pays off. The fact is, you can make good money and save your whole life, but that doesn’t ensure you’ll have enough assets to maintain your lifestyle in retirement or that you won’t waste some of your hard-earned cash on taxes you could have avoided. That’s why strategic retirement income planning is so important—it helps you position your assets to accomplish your goals in the most tax- and time-efficient way possible. After all, what good is all that return if you don’t get to keep it?

One of the most important things to consider is where to invest your money for retirement. A Roth IRA (individual retirement account) allows you to invest post-tax dollars that grow over time—then when you retire, you get to reap the benefits of your investments and their gains, knowing those taxes have already been paid. With a traditional IRA, you invest pre-tax dollars (a strategy that’s advantageous for individuals who want to deduct these contributions) and pay income taxes later when you withdraw the money.

Roth IRAs are great for individuals who want to avoid paying additional taxes in retirement, but there are limits to who can invest in a Roth and how much they can contribute. In this blog, we’ll talk about some of those limitations and alternative ways to minimize your tax burden in retirement.

What are some restrictions for people who want to fund a Roth?

For the year 2023, the maximum amount an individual can contribute to a Roth IRA is $6,500 (or $7,500 if you’re 50 or older). If your income exceeds a certain amount, you’re disqualified from making contributions to a Roth at all. These income limits are based on an individual’s modified adjusted gross income (MAGI), which is your adjusted gross income with deductions and other tax-exempt income added back in.

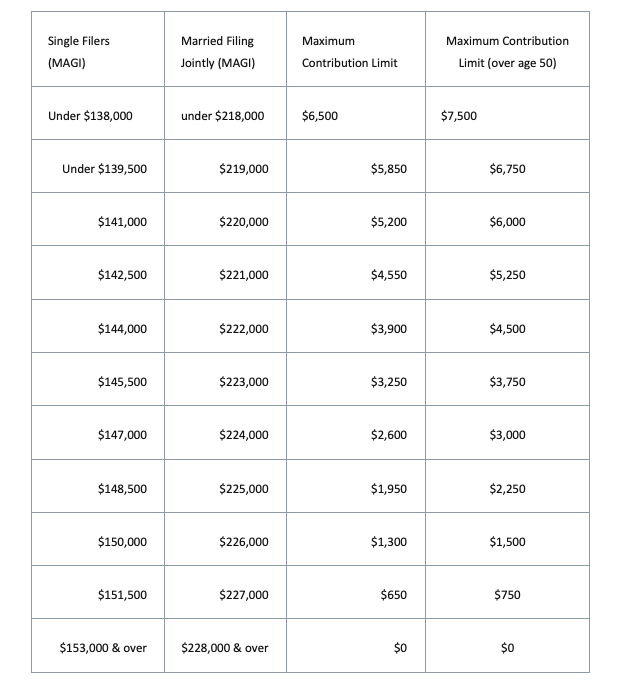

Here’s how those limitations break down:

Roth IRA Contribution Limits (Tax year 2023)

Roth IRA contribution limits 2023

1. You may contribute simultaneously to a Traditional IRA and a Roth IRA (subject to eligibility) as long as the total contributed to all (Traditional and/or Roth) IRAs totals no more than $6,000 ($7,000 for those age 50 and over) for tax year 2022 and no more than $6,500 ($7,500 for those age 50 and over) for tax year 2023.

Individuals can contribute the full $6,000 if their MAGI is less than $125,000. But if your MAGI is between $125,000 and $139,999, that contribution limit decreases incrementally as your MAGI increases. If your modified adjusted gross income is $140,000 or more, you are no longer eligible to contribute to a Roth IRA.

Married couples filing jointly with a MAGI of $198,000 or less are eligible for the full contribution amount ($6,000 per person, $7,000 for individuals 50 or older). If their income is between $198,000 and $207,999, their contribution limit decreases (again, incrementally as their MAGI increases), and once a couple’s modified adjusted gross income reaches $208,000 or more, both individuals become ineligible to contribute to a Roth IRA.

It can be frustrating if you’re a high earner who wants to create tax-free gains later, but luckily, there are some ways around these limits.

What can I do if my income exceeds the contribution limits?

The first option is through your employer—if you have access to a Roth 401(k), you can contribute up to $19,500 (for the 2021 tax year) to that Roth 401(k) regardless of your income level. Individuals 50 or older can contribute up to $26,000 to their employer-sponsored plan.

The second option is to convert money from a traditional IRA or 401(k) into a Roth account. This strategy only recently became feasible. Before 2010, individuals with a modified adjusted growth income of $100,000 or more could not perform a Roth conversion. At that time, the income limit for Roth contributions was $105,000 for individuals and $166,000 for married couples filing jointly —so individuals earning $105k or more had no method of investing in a Roth (unless their employer offered a Roth 401(k)). Since that $100k limit was removed in 2010, individuals can now convert money into a Roth from another account.

In the industry, this is referred to as a “backdoor Roth” because of the roundabout way it allows individuals to leverage this type of account. So while you may hear the term “backdoor Roth,” it’s important to note that this doesn’t refer to a type of retirement account—it’s simply a strategy for contributing to a Roth.

How does this Roth IRA strategy differ from a regular Roth conversion?

Normally, when investing in a traditional IRA, you would deduct those IRA contributions from your taxes in order to lower your income bracket for that year. Then, if you did a Roth conversion, you would have to pay the income taxes on the contributions when you transferred the money from the IRA to a Roth.

But if a backdoor Roth is done correctly, you should have a zero-dollar tax liability. The key is to not deduct the IRA contribution from your modified adjusted gross income—this qualifies the money as a post-tax contribution. That frees you from being taxed on those contributions when you convert them to a Roth.

What about money in my 401(k)? Can I use that for this Roth IRA strategy?

You can also fund a Roth with post-tax contributions from your 401(k)—this includes any money that was contributed without a MAGI deduction. Just like IRA contributions made without a deduction, nondeductible 401(k) contributions qualify as post-tax dollars. You can then take the total of your post-tax contributions and transfer them to a Roth IRA. Something to note, though, is that only the after-tax contributions themselves (not the gains from the 401(k)) can be rolled over to a Roth. You can, however, transfer the gains to a traditional IRA.

That means if you make a $10,000 post-tax contribution to your 401(k) and it grows to $15,000, only $10,000 can be transferred into a Roth. Five thousand dollars (your gains) could be transferred into a traditional IRA or left in the 401(k).

What are some of the pros and cons of leveraging this strategy?

Pros:

- The backdoor Roth strategy allows you to turn post-tax dollars (which would normally be subject to capital gains tax if you invested them elsewhere) into Roth IRA dollars, which gain value tax-free.

- It can be difficult for high-income earners to grow their assets tax-efficiently, and backdoor Roths provide an option for tax-free gains.

- Lots of people have post-tax contributions in their 401(k)s, typically because they’ve over-contributed some years. Backdoor Roths allow you to take advantage of those post-tax contributions and have them grow tax-free (rather than paying income taxes on the distributions if you leave them in a 401(k)).

Cons:

- To set up an effective backdoor Roth IRA, you must forgo the tax benefits of deductible IRA contributions.

- If you have existing IRAs that were funded with pre-tax dollars as well as post-tax dollars, any Roth conversion you make is subject to the IRS Pro-Rata Rule, which could mean you pay taxes on part of the conversion. (More on this below.)

Who can leverage these strategies?

Technically, anyone with earned income can use a backdoor Roth strategy. But it’s only necessary if your modified adjusted gross income (as an individual) exceeds the $125,000 limit for contributing to a Roth IRA.

What are some things to consider before leveraging this Roth IRA strategy?

One thing to note is that if you have both post-tax and pre-tax money in your IRAs, something called the Pro-Rata Rules determines how much of your conversion is taxable. The Pro-Rata Rule involves a bit of math—here’s how it breaks down:

Let’s say you have $75,000 in pre-tax IRA dollars (which are deductible) and you want to make a $6,000 nondeductible contribution to an IRA. Even though you contributed $6,000 of nondeductible dollars, the Pro-Rata Rule takes into account additional factors to determine your taxable rate for a subsequent Roth conversion. The equation looks something like this:

- Current IRA Balance = $75,000

- Nondeductible contribution to traditional IRA = $6,000

- Current IRA balance + contribution = $81,000

- You can’t convert your nondeductible contribution to a Roth as a separate transaction, so your nondeductible balance divided by your total IRA balance determines the percentage of your conversion that is not taxable:

- $6,000/$81,000 = .074 or a 7.4% ratio

- Your nondeductible contribution is then multiplied by that ratio to determine your nontaxable balance. o $6,000 x 7.4% = $444 (not taxed)

- Then, whatever amount is left from your nondeductible dollars is taxed during the conversion. In this case, that would look like this:

- $6,000 – $444 = $5,556 (taxed conversion dollars)

Because of the Pro-Rata Rule, you won’t experience the same zero-dollar tax liability that you would if you had only nondeductible contributions in the account. If you’re considering a backdoor Roth strategy, you’ll want to talk with your advisor to determine if the transaction would minimize your tax burden or not.

What advice would you give a client who’s interested in this type of Roth IRA strategy?

It’s incredibly important to make sure your financial advisor (or whoever manages your investments) and your accountant (or tax advisor) are on the same page. If they don’t collaborate or communicate, your accountant might implement a strategy that your advisor could inadvertently undermine with their own strategies. That’s why it’s important to consult your financial advisor and your accountant to ensure your strategies are cohesive, support your overall goals, and minimize your tax burden.

What’s Next?

If you have more questions about minimizing your tax burden while you prepare for retirement, we’d love to help! We know it can get a little complicated, so we’re happy to discuss your options with you. Just shoot us an email or give us a call!

*Contributions to a Roth IRA may generally be withdrawn at any time without tax consequences. Earnings may generally be withdrawn tax-free if the account is held at least 5 years and withdrawals are made after the account owner reaches age 59 ½. If earnings withdrawals are made before the 5-year period or age 59 ½, income taxes are due, and a 10% federal tax penalty may apply.

[1] https://www.bankrate.com/finance/taxes/